Post by Josh Zinn.

Retired Marshal Will Kane has a problem. Having made a name and reputation for himself as man whom the residents the town of Hadleyville depended upon to establish a peaceful, orderly community, he now finds himself, in a time of personal crisis, essentially ex-communicated from those whose safety he fought so diligently to ensure. Reduced to pleading with longtime friends, forced to defend his recent marriage to a Quaker woman in front of the church, and betrayed by his own deputy, Kane is left humiliated, abandoned, and defenseless by the men and women whose lives he had once sworn to protect. Like a respected employee whose work history and job security are eventually trumped by a company’s bottom line, Kane’s legacy is simply not enough for those whom he served to place their well being on the chopping block along with his. A victim of the very placidity he helped engender, Kane is now a lone man amongst “friends.”

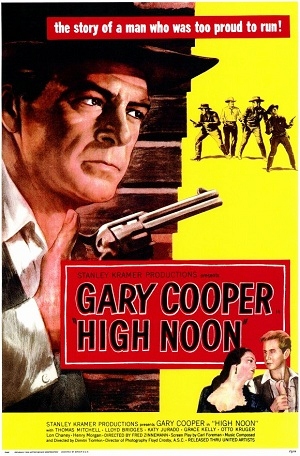

It is within this setting devoid of loyalty and camaraderie that “High Noon,” a classic of its genre, establishes itself as an example of an anti-Western. Rather than feeding into the mythos of larger-than-life men and a “rootin-tootin” landscape popularized in Westerns before it, “High Noon” claims its concerns with the ways in which members of a community might actually respond to one another in light of a larger threat. Instead of guns a’blazing and horses grazing, the town reacts to the impending arrival of Kane’s nemesis, outlaw Frank Miller, by shuttering their windows and closing themselves off from having anything to do with the well-being of one another. Whether this is done out of fear, greed, or in the name of the community’s “best interest,” the eventual outcome is the same: In Hadleyville, it’s every man for himself, regardless of whether someone gets hurt along the way.

This depiction of deceit and disloyalty, while cynical in comparison to other films in its genre, may also be seen as a response to the political climate of the time in which it was made. While comparisons to anti-communist blacklisting efforts (with film community members being forced to turn upon one another in hopes of saving themselves) of the time are certainly warranted, what continues to make High Noon relevant is its unflinching examination of what might lay behind the façade of American idealism. Rather than simply celebrating the pioneering spirit of people who dared to stake claim on a new life for themselves, the film makes the case that, in fact, this entrepreneurial spirit also allows our values and sense of community to take a backseat to doing what needs to be done in order to ensure our own personal success. Since the security of Will Kane’s life rests, in part, on the ability of those around him to stand up for him, it becomes apparent—through the townsfolk’s inaction—the American dream is not collective, but rather a collection of individual desires far less altruistic than it pretends to be.

While some may claim that, like Marshal Kane, they too possess the content of character that would stand up to seemingly insurmountable odds in support of another, the truth of the matter is that human nature often turns a blind eye to problems that are not our own, hoping they will eventually go away. Because Kane had done so much good for his community, he believed his community would respond in kind when he needed help the most. Unfortunately, he is to learn that that train has long since left the station.