Tag Archives: Movie Reviews

Movies in Bed: My Life as a Dog

Post by Josh Zinn.

The boy has no real home, not anymore. Orbiting around the lives of those for whom he feels his existence is now, in one way or another, a complication, his time is spent comparing what he endures with the lot of those whose circumstances appear to have been far worse than his own. It’s a way to get by in this transient life, when you’re viewed more as an attachment, a burden, a nuisance, a pet, than as someone worth knowing. “At least we’re not them,” we tell ourselves, all the while knowing we probably wouldn’t spend so much time thinking about it unless some of their pain resonated with our own.

Lasse Hallström’s “My Life as a Dog” knows what it’s like to feel forgotten about and left to drift towards some unknown oblivion. Like so many of the stories that flow through his mind, the film’s protagonist, Ingemar, is a boy whose happiness and well-being has become an after-thought. Seemingly unwanted, he lives on the outskirts of life, confined to adjunct spaces, with the rest of the world now existing behind shut doors or in memories of better times with his mother. Like Laika, the first dog in space whose fate is ruminated over throughout the film, Ingemar’s idea of his future appears isolated, grim, and hopeless.

To portray this notion of Ingemar being removed from the rest of the world, Hallström places the boy in a series of confined spaces throughout the film. From a drainage tunnel under train tracks, to the cabinet he hides under when his Mother is taken away, to the small spaceship-shaped “funhouse” he hides away in, Ingemar is put in places where he won’t be in the way. Unaware of the complexities of life taking place around him and confused about the changes happening within his own body, Ingemar is frequently trapped within his thoughts, unable to explain or understand what he is feeling. These pockets of solitude, then, become a representation of the darkness—the naiveté—that he must emerge from if he is to find his place in the world.

These allusions to space and rebirth also play a more obvious role in the two attempts Ingemar and his friends make to jettison a makeshift “spacecraft” they find in the old barn. Their first attempt, made when Ingemar is still stuck and holding back from embracing his new surroundings, comes to a halt in mid-air, literally leaving its crew hanging. The second attempt, coming at the end of the film—following a climactic breaking down of the fun house door and Ingemar’s subsequent exorcism of grief and guilt—successfully flies but, even more importantly, comes crashing back down to earth and into a puddle of cow manure. Now knowing he is no longer destined to float away into the ether, Ingemar learns that living an engaged life often means dealing with the crap you’re bound to find yourself in from time to time.

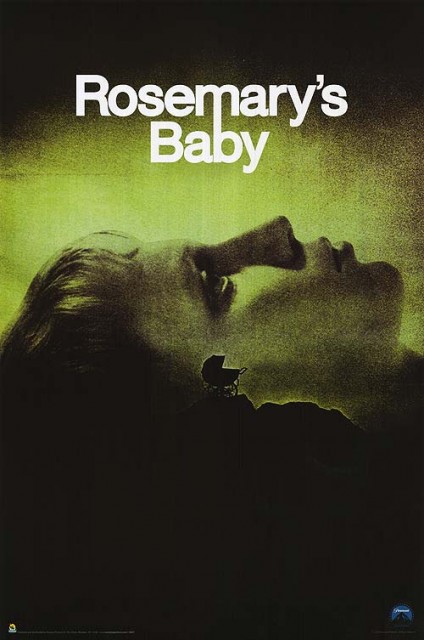

Movies in Bed: Rosemary’s Baby

Post by Josh Zinn.

Walking home today I passed by a woman, no more than forty, weeping over the loss of her beloved sock monkey. I knew it was a knitted primate her tears were shed over due to the fact that she kept exclaiming wildly, “My monkey! My sock monkey! It’s gone!” as she buried herself in the bosom of a friend whose grimacing face conveyed the fractured duality of concern and annoyance that frequently accompanies the consoling of friends. It was like a scene from Beckett—had Beckett ever tackled the all-too-common personal catastrophe known as “Sock Monkey Bereavement.”

The loss of innocence, as you well know dear readers, far exceeds just the complicated conundrums of sayonara sock simians. In an age when colony collapse disorder is robbing the world of honey whilst Honey Boo Boo showers the world with sass, it can be difficult to ascertain what truly matters and why, in the end, we’re supposed to care at all.

Thank goodness, then, for “Rosemary’s Baby!”

Really, think about it: Compared to the miseries that befall Rosemary Woodhouse as she unwittingly sets down a path that will lead her to give birth to the son of Satan, is an overdue electric bill or a missing monkey THAT big of a deal? Sure, it can be a bit of a pain to spend your afternoon on hold, listening to Phil Collins plead to be taken home while the winter’s darkness envelopes your frigid studio apartment, but it’s not as if your husband and a coven of witchy senior citizens secretly made you bring forth the antichrist. It’s all about perspective.

A classic of horror cinema, Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby” takes the idea of forced demonic birth (typically a bummer) and uses it as a metaphor for the inability of our reality to always match up with our hopes and aspirations. Rosemary may think that she’s got the ideal life she always dreamed of, what with her fancy Vidal Sassoon haircut, actor husband, and enormous apartment on the Upper West Side, but the fact of the matter is that the woman has severely underestimated the tenant requirements in her snazzy new co-op. Needless to say, it pays to read the fine print when Beelzebub is on your building’s board of directors.

As you can imagine, life quickly becomes a nightmare for Rosemary as the forces of darkness conspire to give her morning sickness. What’s worse, while she is suffering—saddled with the upheaval of both her dreams and last night’s dinner—her husband is engaging in nefarious games of paranormal pinochle with the witches and warlocks down in Apt. 6B. Where is the humanity!? Alas, life, it seems, is a losing game for Rosemary, with the cards definitely stacked in Ol’ Scratch’s favor.

While it may seem unfair or unmerciful to compare a stranger’s overwrought reaction to the loss of their sock monkey with the bringing forth of the apocalypse, this contrast serves to highlight how all-too-easily we allow the small things in life to dominate our emotions. While the importance of possessions (demonic, sock monkey, or otherwise) should never be underestimated, it’s hard not to imagine a beleaguered Rosemary, cloven-hoofed child nestled against her breast, telling this maudlin monkey mother to go and, “put a sock in it.”

Movies in Bed: It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown!

Post by Josh Zinn.

Though the thrill of Halloween and the festivities and decor the season brings with it still resonate deeply inside me, I must confess to feeling at a loss as to how to properly celebrate this ghoulish holiday as an adult. Truth be told, I find little enchantment in the idea of going to parties where drunken Draculas, kissy-face kitty-kats, and naughty nurses mingle and cavort whilst techno-rave renditions of the Monster Mash thump from cotton cobwebbed speakers. Heck, if I had my druthers Halloween would remain the holiday of my childhood, with trick or treating, haunted houses, and pumpkin carving taking precedent over frat guys dressed as popes pounding Pabsts.

Maybe that’s why today much of my Halloween tradition includes watching as many spooky holiday specials as I can. Because I lose most of my ability to be judgmental when confronted with an animated jack-o-lantern, the majority of these programs have little-to-no artistic merit. Oh sure, there’s probably a way someone could construct a found poem from the dialogue spewed forth in the wittily named “Fat Albert’s Halloween Special,” but I merely prefer to sit back and allow America’s second-favorite rotund representative of the inner city (tip of that hat to you, Biggie) to enlighten me through shoddily animated examples of the proper ways to inspect Halloween candy.

Occasionally, however, certain holiday cartoons are able to excel beyond their “sponsored by Pudding Pop” pedigree. With its lovingly neurotic and sincere tone, “It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown” is just such a feature. In fact, other than the previously reviewed “The Worst Witch,” it may rank as my favorite Samhain special.

Here’s what you need to know: no one likes Charlie Brown, yet that doesn’t stop him from wishing everyone would. Here’s what you also need to know: No one else believes in the Great Pumpkin, yet that doesn’t stop Linus Van Pelt from wishing that the grand gourd of the night will pay a visit to his most sincere of pumpkin patches.

While I am aware that, on the surface, this may sound like a story about disillusionment and the realties of dementia and class-based ostracism, what makes this Halloween tale so charming, disarming—as well as a boon for urban pumpkin farming—is its lack of pretension and its utter belief in the emotional and social worth of childhood desires. That may sound like a heavy way to describe a bunch of Peanuts, but what separates “It’s The Great Pumpkin Charlie Brown”’s wheat from the rest of the cartoon chaff is the way in which it honors and acknowledges the fears and foibles that plague the minds of the under-10 set. These characters pursue their dreams not to teach viewers the proper way to look over a mini-Snickers bar, but rather to show them that being different doesn’t stop you from still being worthwhile.

Perhaps, then, it’s Ol’ Chuck and Linus who showed me that, even in my old age, it’s okay to want a Halloween free from the noise of one-too-many Long Island Iced Tea-induced Alice Cooper karaoke contests. Me? I’d rather be sittin’ in a pumpkin patch, waiting to hear something go bump in the night.

Movies in Bed: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Post by Josh Zinn.

The street signs of Sleepy Hollow have headless horsemen on them. So do the police cars, garbage trucks, and natural gas meters. In fact, I’m sure a myriad of public utilities take part in celebrating and cashing in on the famed decapitated equestrian whose midnight rides of terror helped transform their humble hamlet into the Halloween haunt of the Hudson hinterlands. Perhaps Washington Irving hadn’t imagined his creepy creation would one day come to signify the call to arms for the men and women working for Sleepy Hollow’s sewage system, but crappier things have happened in the name of public works—just ask the folks who named Flushings.

If one were to ask the Headless Horseman himself—hey, he might know sign language…even though he doesn’t have eyes—what moments in his fictional life truly felt like a misappropriation, however, he’d probably tell you about the time I purchased a key-lime flavored latte (complete with crunchy graham topping!) from a Sleepy Hollow coffee shop. Or the Mexican restaurant named after him that served my friend and I a salad consisting of a HEAD of lettuce alongside a terrine of “bloodied” French dressing. Oh yes, and then there was the time Bing Crosby came to town…

Disney’s animated version of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” starring Crosby as beleaguered schoolteacher Ichabod Crane, is a milder take on Irving’s allegory of foreign-bred superstition and tradition mingling with the bravado, boldness, and greed of the then-new America. By milder, I mean that Ichabod spends much of the cartoon either singing sweet dulcimer notes to the local housewives in an attempt to lure them of their chicken dinners or by balladeering Katrina, the beautiful daughter of the wealthiest man in town, in order to fill his pocketbook. Horror only exists on the outskirts of this Sleepy Hollow, with creepiness taking a backseat to Crosby’s crooning.

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” isn’t a bad film by any means, but in shifting its focus away from the terror of Tarrytown and onto the soothing vocal abilities present in Crosby’s portrayal of Crane, Irving’s supernatural story mutates into a pageantry of phthongal pedagoguery better fit for a USO function. Truth be told, there’s little fright to be found in a film where, for the majority of its length, fanatical females fight for the chance to feed a fair-weather philanderer with the voice of a lounge singer. Sure, the Horseman finally rears his hea… neck near the cartoon’s finale, but until then any pervasive sense of dread has been replaced by questions of whether white Christmases happen even for the headless.

Perhaps, then, the Horseman-emblazoned signs, logos, and salads of today’s Sleepy Hollow are a reclamation of the sinister story that put their town on the map. While there’s nothing wrong with a little Bing to lift one’s spirits, it’s best to remember the spirit at the heart of Irving’s story struck a far more horrific note.

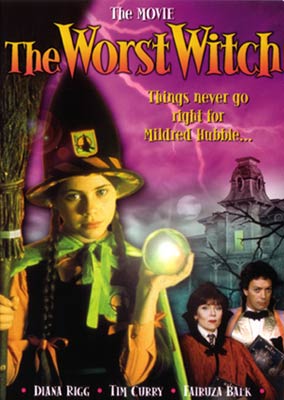

Movies in Bed: The Worst Witch

Post by Josh Zinn.

Back when I was in high school, the school district thought it appropriate to bring in the occasional motivational speaker to come and regale students with metaphorical stories of success that might inspire them to find newfound meaning and purpose to the daily machinations of their public education. Though speeches from firefighters and sweaty, rotund local councilmen were the de rigueur for these assemblages of student body, one day in late October television talk-show host Montel Williams came by to pay us a visit.

A C-list celebrity attempting to coax A’s out of D-list small town, Montel shone like a 25-watt bulb, illuminating students on the dangers of staying in the scholastic dark. If nothing else, his words of wisdom got me out of P.E. and the first fifteen minutes of my dreaded Algebra class. If the purpose of Montel’s visit had been to brighten our day, in my eyes he was an unqualified success.

The girls attending Miss Cackle’s Academy of Witches know too the excitement and allure of having “sinspirational” speakers come before them. After all, while it’s certain that Powders & Potions class can be intoxicating and bubbling over with excitement, there is nothing quite so effervescent as when the Grand Wizard comes to pay the school a visit—especially when the Grand Wizard is played by Tim Curry.

Based upon Jill Murphy’s series of books of the same name, “The Worst Witch” is not just a Halloween special; it is THE Halloween special by which all other Halloween specials should be judged. Existing in that rarified realm where quality of production is superseded by the charm of intent, this tale of a clumsy witch-in-training named Mildred Hubble has little to offer in the way of production value or Tom Stoppard-esque dialogue. Instead, what it does is magically transport the viewer to a time in the mid-80’s when the trials and tribulations of adolescent sorcery were best-conveyed using bad off-off-Broadway songs and the special effects team from the latest A Flock of Seagulls video. Needless to say, Harry Potter she ain’t.

While “The Worst Witch” may be lacking in the whiz-bang of its recent kid-with-a-wand brethren, where else can one find Charlotte Rae, everyone’s favorite housemother (Mrs. Garrett) from “The Facts of Life,” playing dual roles as both a good and bad witch? Or, for that matter, a young Fairuza Balk, before “The Craft” had cast its patent leather spell of Nine Inch Nails gothic fashion upon her? And let us not forget the Grand Wizard himself, Tim Curry, whose Halloween visit sends the entire school the entire school into a tizzy and helps teach a little girl the importance of believing in herself through the use of songs crafted from the finest in rhyming dictionaries. Bewitching.

It’s not for naught that Montel and “The Worst Witch” remain such important pieces of my adolescent experience. Seemingly unrelated, they are curios of a time when the lowered expectations of my youth kept boredom at bay. Twenty years later, however, Montel is no longer on the air while “The Worst Witch” remains a Halloween favorite. Had Montel found his own way to rhyme tambourine with “Begin the Beguine,” perhaps he’d be singing a different song.