Post by Josh Zinn.

A code of conduct listed in the Disneyland new employee manual states, “All cast members must appear calm, content, and capable while working. At Disneyland a pleasant smile is a personality trademark that we use all the time in greeting, directing, and making our guests feel comfortable. You don’t have to laugh, just smile. Don’t be a Gloomy Gus or a Grouchy Gertrude.”

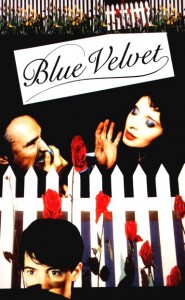

During the opening minutes of David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet,” the town of Lumberton appears to be an idyllic place, the kind of community where even Grouchy Gertrude’s cannot resist a grin or two. As hyper-saturated flowers sprout through the ground, children excitedly scurry to school, and fire trucks cut through the dewy morning haze, all seems right with the world. Like a neighborhood that has emerged from some promise of sanctity made by “Ozzie and Harriet” and “The Donna Reed Show,” the artifice of its mise-en-scene is intoxicating and familiar not because it resembles the world we live in—or even necessarily desire to—but because it is a portrait of what we’ve been told our lives should aspire to be.

Underneath its façade, however, not everything is so squeaky-clean. As the opening sequence continues, Lynch introduces elements of the grotesque amidst this artificial environment. A gun appears briefly on a television; a man collapses while watering his lawn; and, as the camera moves past his still body, cutting through the grass, an underworld of insects is discovered writhing beneath the blades. Presumably they have always been there, but like so many things eventually uncovered in this town, their existence has been buried under the layers of innocence, tranquility, and self-imposed naiveté Lumberton’s reputation is built upon.

This duality in reality, of experiencing and acknowledging the darkness that thrives beneath the manufactured gloss of our clichéd suburban ideals, is the heart of “Blue Velvet’s” story. Because Lynch’s introduction of Lumberton in this sequence is so steeped in the kind of Americana nostalgia where every shot is bathed in filtered light and moves in slow motion, the impression given is that it exists outside of reality, in a realm where Dalmatians really do ride in fire trucks. Neither dream nor truth, the perfection Lumberton appears to exhibit may be seen, then, as the culmination of good intentions and sheer will triumphing over desire and emotion. Like a rehabilitated drug addict, the town is “good” so long as it is able to maintain its behavior. Beneath its fragile exterior, however, its demons continue to look for ways to claw themselves free.

Because “Blue Velvet’s” story descends into what may be construed as the underbelly of Lumberton, it becomes apparent that Lynch is both examining and satirizing peoples’ need to keep up appearances. Quickly exposing both the audience and his characters to the cracks that have begun to riddle the artificial, too-good-to-be-true foundations of the town, Lynch injects the film with a freedom to be unreliable in its depiction of truth. Here, regardless of what may appear to be a meticulously created reality, other forces are always at work shaping the landscape. One simply needs to keep their ear (sliced off or not) to the ground to listen for them.

Like Disneyland, a smile may go a long way in Lumberton, but that doesn’t necessarily mean everything is okay.